“I was born delusional,” said Chris Ayres, Princeton’s head wrestling coach, earlier this year. “But I think — I really do — that delusion is a good thing.” He just proved his point. At Tulsa, Oklahoma’s NCAA wrestling tournament last month, Ayres pulled off one of the least likely turnarounds college sports has ever seen.

“No one believed in this,” said Ayres, beer in hand on the tournament’s final night. “No one except the people in this room.”

An hour earlier, 125-pound senior Pat Glory had beaten Purdue’s Matt Ramos 3-1 to become Princeton wrestling’s first national champion in 72 years. That led the Tigers to 13th overall, their best finish since 1951. For the third time in three seasons of Ivy League competition, Princeton wrestling was a top-20 team. It had last gone top 20 in 1985. When the clock timed out on Glory’s win, Ayres almost cried. Glory actually did — and here, at Princeton wrestling’s downtown afterparty, he still kept choking up. Bartenders mixed blood-orange margaritas for the 70-odd former and current Princeton wrestlers who’d seen the turnaround through.

In the last five years, Princeton’s program has blown past milestones at warp speed. It won its first Ivy League championship since 1986, logged its first seasons with three, then four All-Americans; its second year with a national finalist since 2002, and its first time ever fielding two. Eight Princeton wrestlers had ever achieved All-American status before 2016. Five have since. Now this.

Almost everyone involved in a statistic was in the room. There was John Orr, national finalist of ’85, grinning ear-to-ear in a tiger-print blazer. Ayres’ first All-American, Brett Harner ’17, talked crypto to two traders. Matthew Kolodzik ’21, Princeton’s first top-ten recruit, squirreled in a corner. Under an orange-and-black balloon arch two senior wrestlers scrapped, their drinks at their feet. People wanted to talk. “You’re on one of the greatest sports stories of all time,” slurred one former heavyweight. A 149-pounder cut in: “The greatest, bro. The greatest.” (It’s not just them. InterMat last summer called Princeton wrestling ‘the best turnaround in college sports.’) “It’s not a dream,” said assistant coach Joe Dubuque. “It’s not a vision. This shit’s real.”

Ayres, beaming, leaned against a corner wall. “Can you imagine this party if we hadn’t got a champ? With these frickin’ balloons? Holy Christ. But we believe. We buy the balloons. In this party, in this program. I just believe.”

Eff you, not today

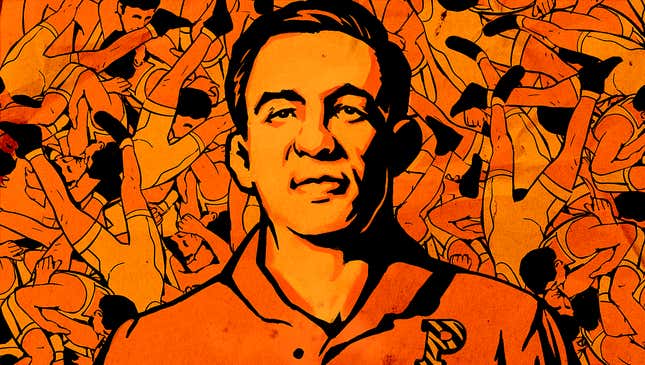

Ayres is 49 and ropy, workshopping a catchphrase at all times. “Gentle pressure, relentlessly applied” is a current favorite. In Tulsa, “Doubt: eff you, not today” got some air. He moves with such restless intensity he might be spring-loaded. Ayres looks distinctive until he’s in a room of wrestlers. Then you realize the squashed nose and square jaw are the sport’s features, not his. He came to Princeton in 2006, at 32, from an assistant job at Lehigh, which has produced 159 All-Americans (including Ayres, in ’99) and 28 national champs. Princeton was the worst program in the country. FloWrestling called it a “bottom dweller.” The average DI roster had 33 athletes. Princeton had 16, redshirts included.

Ayres lost his first 37 meets and made the scale of his delusion clear. Through nine straight losing seasons he insisted that he could will Princeton into a wrestling school, with a national title and an All-American trend. The five-year goals in his first coaching plan were straightforward, including: 2. Change Culture of Team; 6. A National Champion.

“Chris was such an eager young guy,” said Orr, the ’85 finalist, now a program booster. “He had all these big visions. I just listened, encouraged him. I couldn’t bring myself to tell him he was dreaming.”

Iowa, Iowa State, Oklahoma, and Oklahoma State have together won 75 NCAA tournaments since 1928. Add PSU to the mix and the total jumps to 85. Texas’ small-town boys played football. In Eugene, they ran. Each year’s top wrestling recruits come from, and largely stay in, the states where they wrestled: Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Ohio. For 70 years Pennsylvania’s best wrestlers have come from the Lehigh Valley, the former home of Bethlehem Steel. Farmers and coal miners passed the sport to their sons and grandsons. Rates of girls’ wrestling have tripled in the last 15 years, and the women’s NCAA division is one vote away from the status as a full-fledged sport.

Still — wrestling championships are the rare event at which women walk right into their restroom, and the men’s line stretches out the door. Said one Princeton alum, class of 1980: “The most testosterone in the country is in this arena right now.” Wrestling skews rural, working class. Donald Trump could have gone to a second-round March Madness game on the 18th. He chose Tulsa’s finals, where he thumbs-upped the roars of ‘four more years.’

So think “wrestling stronghold,” and Princeton doesn’t come to mind. This is a sleepy, brick-and-ivy town with one dark bar to speak of. An Hermès store is opening next year. Seventeen percent of this year’s freshmen are first-gen college students, but the university’s prep school optics are hard to shake. At commencement each spring, the faculty choose one outstanding student to deliver a class speech — in Latin. The acceptance rate is 4.4 percent. One South Dakota State alum leaned to me, mid-interview in Tulsa, to interrupt: “I can’t believe Princeton finds wrestlers with IQs so goddamn high.” At the end of Jersey’s wrestling season each March Rick Fortenbaugh, wrestling reporter, awards 50-something superlatives in the Trentonian’s back section. In 2020, he gave Funniest Sign to one that read “Princeton is a wrestling town.” He kept the commentary brief: “Yeah right.”

So Ayres had neither history nor culture on his side. And yet: “I just didn’t see a reason why we couldn’t pull this off.”

Trash talk and hype videos

It helped that he had a loyal network in his corner. Princeton wrestling has a steady Wall Street pipeline and a commitment to calling its alumni web a family. One member is on-again, off-again billionaire and bitcoin bull Mike Novogratz. Novogratz, 58, made it twice to NCAAs at 150 pounds and never placed. (“I still think, monthly, about the guys who beat me.”) Now he is the program’s biggest donor. “I was always confident,” he said. “Resources don’t fail.” Joe Tsai has seeded Yale lacrosse. John Ruiz has set the NIL bar sky-high at Miami. Princeton dominates in a traditionally blue-collar sport thanks in part to a billionaire booster famous for his helicopter flyovers. It helped that Ayres was willing to stand out. Princeton runs a ruthless social media campaign. Ayres churns out hype videos and trash-talks other coaches and their athletes in interviews and tweets. “Attention is attention,” he said.

Ayres in high school wanted a state medal. He never placed in Jersey’s tournament. In college he wanted a national title. He had a stunning run — but his highest place was sixth. Post-grad, he wanted a national team spot. He was cut at trials. “The heartbreak stays with you,” he said. “But you get up and you fight.” The attitude’s contagious. Ask Ayres’ athletes why they believed the promises he made and, inevitably, they say they just believed that he believed. The season before 2016 All-American Brett Harner joined, Princeton went 2-13. “I was an impressionable 18-year-old,” said Harner. “And he was all in.”

“I was trash,” said one slow-blinking heavyweight from the thick of Ayres’ slump. “But he’s very believable.”

Ayres is Ayres

And it helped above all that Ayres is Ayres. From a mediocre career at North Jersey’s Newton High he walked on, at 157 pounds, to Lehigh’s team. He set a program record there for career wins (120) and season ones (39). He MVP-ed twice and made All-American his senior year. “I just believed I could be good,” he said. “I thought there was no way I could put the work in and have it not pay off.” To him, the equation really is that simple. Conviction plus discipline guarantees success. He is never far from a quote — his own or someone else’s — to that effect: “Rule your mind or it will rule you” (Horace). “Perseverance is the hard work you do after you get tired of getting the hard work you already did” (Gingrich). “If you’re disciplined, you can’t fail” (Ayres). That actually he has failed a great deal doesn’t interfere with the philosophy.

Interview any wrestler and he’ll tell you the same thing: an outsider can never understand his sport. “It shouldn’t even be called a sport,” said Ayres. Defeat in a wrestling match means walking into a fight alone, on purpose, in public, and getting beat. A lifetime of training boils down to seven minutes nearly naked, hungry, one-on-one. The sport’s brutality, and its solitude, stand out. “Once you’ve wrestled, everything else in life is easy,” is legendary Iowa coach Dan Gable’s famous line. In no other sport have I seen so many grown men cry.

Ayres cannot get enough. He says he was born delusional; saying he was born a wrestler gets at the same thing. Discipline and blind conviction are the qualities wrestlers like to say matter on the mat. “We’re tough kids, wrestlers,” Novogratz said. “There’s no room for fear, no room for doubt. Even when there probably should be.” Ayres stopped wrestling after his run at U.S. World Team Trials in 2002. But his 17-year career at Princeton precisely imitates the cadence of the sport. In 2006 Ayres walked into a losing proposition with all the odds against him. In public he lost, and lost, and lost. And with discipline and blind conviction (plus Wall Street dollars and hot-blooded assistants, both of which he thanks at every turn) he muscled this turnaround to life.